If each brand and bottle of soy sauce represents a specific Chinese dialect…that would be pretty accurate. If you can find more than one type of soy sauce at a store the demand for the variety suggests that there’s more than one type of Chinese person to cater to, and more than one Chinese community that shops there or make up the community. Chinese culture, cooking styles and taste preferences widely vary based on the type of Chinese cuisine, geographic location, time, availability of resources, and lifestyle.

Shopping for Chinese 豉油(soy sauce; m: chi you; c: si you) is puzzling even for Chinese people. The exponential options offered in the condiment aisles at supermarkets tend to make it hard to catch up; each brand modifies the soy sauce recipe in their own way, resulting in subtle differences between each bottle. So, which bottle to purchase exactly?

Despite the overwhelming number of options out there, typical Chinese families frequent their pantries for only two types of soy sauces: light and or dark. According to a couple of seniors who were shopping in Chinatown, soy sauce is a very versatile condiment perfect for any season used in, but not limited to, Chinese cuisine.

For an authentic and traditional flavor, opt for both the traditionally fermented, or naturally brewed “生抽” (Light; m: sheng chou; c: saang chao) and 老抽 (Dark; m: lao chou; c:loh chao) soy sauces. Light soy sauce is preferred for adding a light umami flavour in a hot bowl of soup noodles. 頭抽 (Premium; m: tou chou; c; tao chao) is the highest quality of light soy sauce that is primarily used for dipping things like Atlantic surf clams and pulled pork. Dark soy sauces are much more pungent and staining, ideal for marinating in that healthy caramel glow when it comes to barbeque meats.

Below is a basic list of Cantonese pantry staples. Remember to read bottle labels and you’ll avoid ending up with soy sauce lookalikes (that are actually cooking vinegars and wines in disguise):

| 頭抽 P r e m i u m | 生抽 L i g h t | 老抽 D a r k |

|---|---|---|

| Taste: the richest aroma, natural fresh complement, clean clear Words to look for: #premium, #light, #traditional, #fermented, #naturallybrewed, #頭抽 Types of Chinese cuisine likely to use this: Cantonese (Guangdong and hong kong), shandong, anhui, fujian Local ingredients it would pair well with: Atlantic surf clams, pulled pork, beef brisket Effect(s) on cooking: deodorize fishy smells, create a contrast between the taste of soy sauce and the piece of food being dipped | Tastes: delicate saltiness Words to look for: #light, #traditional, #fermented, #naturallybrewed, #生抽 Types of Chinese cuisine likely to use this: Cantonese (Guangdong and hong kong), shandong, anhui, fujian Local ingredients it would pair well with: wintermelon, melons, vermincelli, thin noodles, pork, chicken, sesame oil Effect(s) on cooking: generate light umami, synergize different flavours | Tastes: pungent, mature, sweeter, darker Words to look for: #dark, #traditional, #fermented, #naturallybrewed, #老抽 Types of Chinese cuisine that would use this heavily: Sichuan and Hunan for the spicy pungent flavours Local ingredients it would pair well with: beef, pork, chicken, seafoods, other meats, tea eggs Effect(s) on cooking: colorize, disinfect meats with its saline qualities, heating |

*Note: If you see a bottle that says regular soy sauce, it’s probably a blend of both light and dark soy sauces.

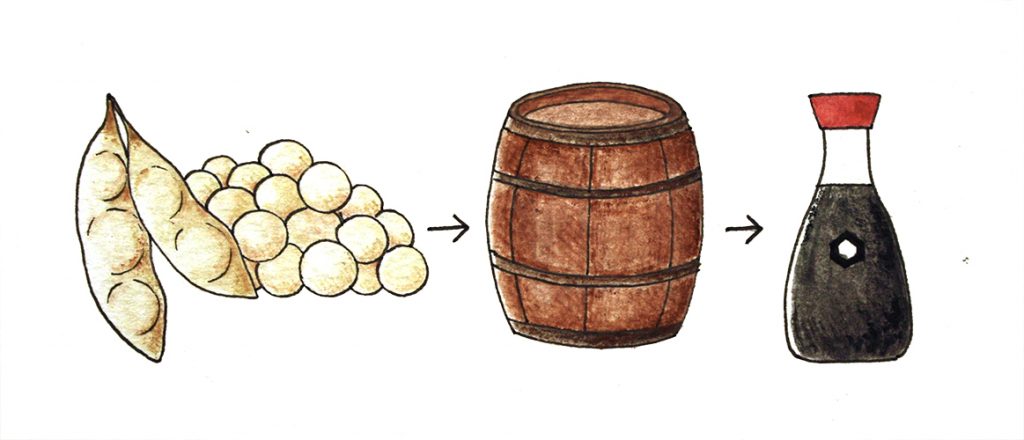

How Chinese Soy Sauce is Made

Soy sauce gets classy. Imagine a barrel of soy sauce sectioned into 3 layers. The top two layers are 頭抽 and 生抽 -the light types of soy sauces. 頭抽 is at the surface of the barrel and gets extracted and bottled up first; next is 生抽. Dark soy sauce 老抽, is the found in the third, or bottom layer. Light and dark soy sauces are describing and referring the opacity, viscosity, and production methods of the two main types of soy sauces.

The traditional way of making soy sauce, also known as a natural brew, is still used today; it’s a method involving the fermentation of soybeans, wheat, salt and water. This process that can take up to a few years before getting filtered and bottled. Each process allows the ingredients to flavour the sauce with the acidity, sweetness, saltiness, and bitterness that create the aromatic umami* experience. Modern technology has made way for new variations, referred to as chemical soy sauces, whereby ingredients go through hydrolysis to form soy sauce in as quick as three days!

*Umami is a borrowed word from the Japanese, describing a savoury flavour that can be found in brothy soups.

Cooking Tips

1 The lighter the soy sauce is, the more easily it will oxidize. However, each glass bottle of soy sauce has a shelf life of two years before opening (as long as you store it in a cool, dry place away from light). So don’t be afraid of trying different soy sauces, but you may want to stick with one you like. It doesn’t take too long to finish a bottle. My grandmother sticks to the basics. She uses up light and dark bottles of soy sauces quickly for dipping, cooking, marinating, braising, stewing, pickling, and salting.

If you’re curious, though, you can tell when soy sauce is no good if its thickness and color start to change due to oxidization.

2 Don’t be afraid to mix and blend things up! Add soy sauce to other soy sauce, soy sauce to other sauces, and soy sauce to your ice cream. Experiment! Find what clicks.

*Reminder: If you see a bottle that says ‘regular soy sauce’, it’s probably a blend of both light and dark soy sauces.

To change the smell and taste of soy sauce, layer in flavours into the full-powered dark soy sauce by sprinkling fresh ingredients used in regional cuisines like: cloves, chives, cilantro, dried shrimp, ginger root, garlic, white pepper, sesame oil. These ingredients can all be found in local Chinatown grocers and dried goods stores for a new aroma.

Beyond colour: Demystifying the surface sameness to reveal cultural differences among the Chinese.

It’s difficult to tell one soy sauce from another without the labels and packaging, but I think it’s important to note that each bottle is unique. There is diversity in Chinese cuisine just as there is diversity in the culture itself. Similarly, the variations derived from the experimental culinary uses of soy sauces show which part of China’s geography and Chinese culture a particular dish comes from and its influence on other cuisines. Chinese cooking styles and taste preferences change based on geographic location, time and place, availability of resources, culture, and lifestyle. For example, in Sichuan and Hunan cuisine, dark soy sauces are likely more popular than light soy sauces in order to achieve the renown strong, pungent, spicy and numbing flavours. Shandong cuisine would use lighter soy sauces to bring out the freshness of their seafood dishes. Anhui and Fujian are all about mountain ingredients found in the wild, where light soy sauces would be ideal in order to intensify aromas. Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Cantonese (think places like Guangzhou and Hong Kong) prefer sweetness over saltiness, whereby light soy sauces are most sensibly used. Outside of China, soy sauce flavoured ice cream has been discovered in Japan, where vanilla magically becomes salted caramel. Seriously, soy sauce is making a hit at different geographical locations on one’s taste buds!

Adaptations

In early Canton China and Hong Kong, the fishmonger community had constant access to fish which explains the rise of seafood inspired soy sauces. Similarly with the materials they frequently had access to, butchers would mix together sugar and soy sauce to create the now famous Chinese BBQ pork sauce.

Interestingly, soy sauce used as a condiment in different cuisines puts into perspective the impact Chinese ingredients have had on food culture throughout the world. Think of Worcestershire sauce – there’s soy sauce in there!

Preservation

In all cuisines, sauces and condiments have resulted from techniques used in preserving foods and also to make spoiling food more palatable. For thousands of years and still today, meats, seafood, fruits, vegetables and grains are crushed and fermented in vinegar or brines, water saturated with salt, which would later become what we refer to today as “sauce” and even wines. Ketchup is essentially preserved tomatoes. Strawberry jam is the fruit itself cooked in cornstarch and sugar. Hot sauce is mashed up chili peppers, and so forth. Examples of more modern methods would be canning, refrigeration, freeze frying, and fermentation using lactic acid bacteria. Canned peaches are popular in the Midwest as is Sauerkraut in Germany, and Gimchi in Korea. Soy sauce was discovered from grain preservation techniques. The abundance of soybeans made it easy to create a refined product from grains.

Looking back, my confusing soy sauce shopping experience has enabled a newfound respect and understanding for the intergenerational and intercultural community that is Chinatown. It’s a perspective never found in the Social Studies textbook facts I was tested on growing up. It’s admirable how many communities of overseas Chinese immigrants have contributed to each country’s culture… through soy sauce and its various adaptations. And it’s fascinating that something as commonly used like soy sauce is overlooked, despite its embeddedness in the way we share culture through food every day of our lives regardless of culture. Truly, the vast and varied Chinese community has contributed so much more than just the construction of the trans-Canada railroad system and mining 50% (reference research here) of the world’s gold.